Four young children have gained life-changing improvements in sight following treatment with a pioneering new genetic medicine through Moorfields Eye Hospital and UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, with the support of MeiraGTx.

The children were born with a severe impairment to their sight due to a rare genetic deficiency that affects the 'AIPL1' gene. The condition means those affected are born with only sufficient sight to distinguish between light and darkness. The gene defect causes the retinal cells to malfunction and die, with children affected being legally certified as blind from birth. The new treatment is designed to enable the retinal cells to work better and to survive longer.

The procedure, developed by UCL scientists consists of injecting healthy copies of the gene into the retina, at the back of the eye through keyhole surgery. These copies are contained inside a harmless virus, so can penetrate the retinal cells and replace the defective gene.

The condition is very rare, and the first children identified were from overseas. To mitigate any potential safety issues, the first four children received this novel therapy in one eye only. All four saw remarkable improvements in the treated eye over the following three to four years, but lost sight in their untreated eye.

The outcomes of the new treatment, reported in The Lancet, show that gene therapy at an early age can dramatically improve sight for children with this condition - one that is rare and particularly severe. Successful gene therapy for another form of genetic blindness (RPE65 deficiency) has been available on the NHS since 2020. These new findings offer hope that children affected by both rare and more common forms of genetic blindness may in time also benefit from genetic medicine.

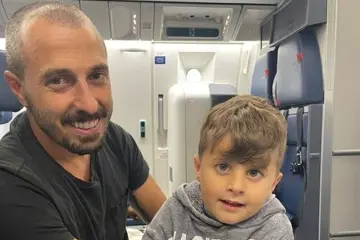

DJ and Brendan from Connecticut, USA, the parents of one of the children, Jace, shared details of their treatment.

When Jace was two months old, Dad Brendan said to Jace’s mum DJ: “At what age should he start looking at us?” They then contacted clinicians they knew, and were referred for tests to see if the cause could be neurological or genetic.

He continued: “We spent months talking to doctors, hearing their hypotheses, until a retinal referral confirmed he has an aggressive form of LCA (Leber Congenital Amaurosis). By chance, at a charity’s conference, we met Professor Michaelides, who told us of his research work at Moorfields, and we were accepted for this experimental treatment”.

Mum DJ added: “After the operation, Jace was immediately spinning, dancing and making the nurses laugh. He started to respond to the TV and phone within a few weeks of surgery and, within six months, could recognise and name his favourite cars from several metres away; it took his brain time, though to process what he could now see. Sleep can be difficult for children with sight loss, but he falls asleep much more easily now, making bedtimes an enjoyable experience.”

Brendan concluded: “We are so grateful for this opportunity, and for the care he’s received; we feel we have friends now at Moorfields. When first offered the chance to participate, we wanted to give him everything we could, for him to successfully navigate the world. We also understood the huge implications for future research, and how participating could help others. It has been a phenomenally positive experience, and the results are nothing short of spectacular.”

The team is now exploring the means to make this new treatment more widely available.

Professor James Bainbridge, consultant retinal surgeon at Moorfields Eye Hospital and professor of retinal studies at UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, said: "Sight impairment in young children has a devastating effect on their development. Treatment in infancy with this new genetic medicine can transform the lives of those most severely affected."

Professor Michel Michaelides, consultant retinal specialist at Moorfields Eye Hospital and professor of ophthalmology at the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, commented: " We have, for the first time, an effective treatment for the most severe form of childhood blindness, and a potential paradigm shift to treatment at the earliest stages of the disease. The outcomes for these children are hugely impressive and show the power of gene therapy to change lives.”

Professor Robin Ali, UCL Institute of Ophthalmology and King’s College London Centre for Gene Therapy and Regenerative Medicine, added: “This work demonstrates the importance of UK clinical academic centre manufacturing facilities and MHRA (UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency) Manufacturer’s ‘Specials’ Licences (MSLs) in making advanced therapies available to people with rare conditions.”

The treatment was developed and manufactured at UCL under an MSL held by UCL. MeiraGTx supported production, storage, quality assurance and released and supplied it for treatment under their MSL.

The procedure to administer the treatment to the affected children took place at Great Ormond Street Hospital. The children were assessed in the NIHR Moorfields Clinical Research Facility, and the NIHR Moorfields Biomedical Research Centre provided infrastructure for the research.

The work was partially funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), Meira GTx and Moorfields Eye Charity, thanks to the generosity of donors. Moorfields Eye Charity has also supported Professor Bainbridge’s work as the professor of retinal studies, enabling the expansion of this programme of experimental medicine including the initiation of gene therapy trials.

Find out about genetic therapies and how to access genetic testing here.

Read about our work on LCA2, which is now available on the NHS here.

To find out how to participate in clinical trials at Moorfields, visit ROAM.